Squashing Your Pull Requests

TL;DR: Most pull requests should squash down to a single commit with a well-written message explaining why a change is happening.

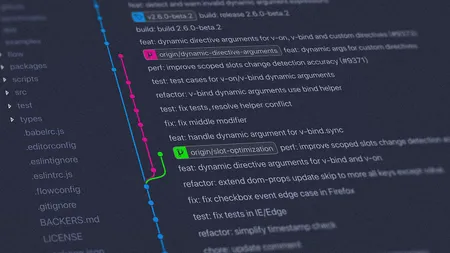

Image credit: Yancy Min

As a general rule, when merging a pull request from a feature branch with a messy commit history, you should squash your commits. There are exceptions, but in most cases, squashing results in a cleaner Git history that’s easier for the team to read.

For context, our team uses a version of Git Flow, which means team members do their work in a feature branch. Most feature branches are short-lived, and there’s only one developer committing work to it. When the work is ready for review, they make a pull request back to the parent branch. The team will review the pull request, and once it has been approved, it gets merged, and the feature branch is deleted.

The advice I give in this post may be less relevant if you don’t use feature branches like this. Long-lived feature branches with many developers committing, or branching again from the feature branch will complicate matters. As usual, there’s no one right answer about how to use Git. The best workflow is the one that works for your team.

For demonstration purposes, I’ve created a Git repo with a pull request containing multiple commits. It’s a bit of a mess. In my experience, most pull requests look like this by the time they’ve been approved.

There’s often a handful of incremental commits reflecting the original work the developer did. Then come a few minor commits fixing typos or lint errors. There may be some commits addressing code review feedback. There might even be a revert of some code that needed to be removed from the pull request (and then a revert of the revert!). By the time it gets approved, your pull request has probably become a mess of dozens of commits, with unhelpful messages like whoops and sigh, lint fix.

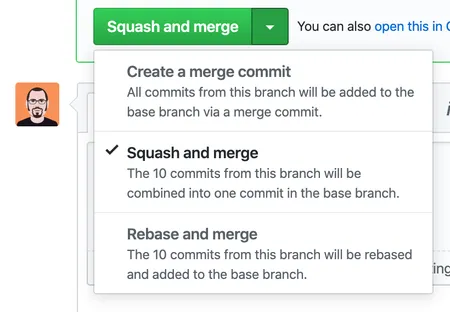

Now, you’ve got three options for how to merge it: You can make a merge commit, you can rebase and merge, or you can squash and merge. All three are useful in different circumstances. Let’s review:

Screenshot of the GitHub merge options: create a merge commit, squash and merge, or rebase and merge.

Merge Commit

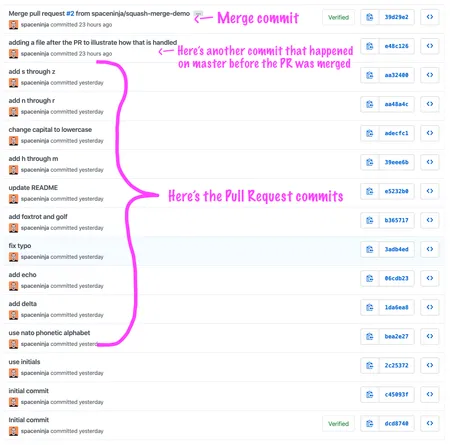

Making a merge commit is the default option in GitHub. When you choose this option, your commit history will be retained exactly. Your commits will be interwoven with any other commits made on the parent branch. Then a new commit will be added at the very end, with a message like “Merge pull request from feature branch.”

Screenshot of Git history showing a large group of pull request commits, followed by a commit that happened on master before the pull request was merged, followed by a merge commit.

Note that all your messy incremental commits are still there. And even if your branch only contained a single commit, there will still be a merge commit added.

Making a merge commit is useful for a situation where you want the history to reflect that two branches were merged. In our team, whenever we make a release branch, multiple developers will make commits to that branch over time. Once the release is done, we’ll merge the release branch back into the primary development branch using a merge commit. In that case, the “Merged release 13” commit is useful.

However, in the use case we’re solving for — a developer merging a short-lived feature branch with no dependencies — that history is pointlessly noisy. All those fix typo commit messages don’t add anything to history, or to your team’s understanding of how this feature was added. So what’s our next option?

Rebase and Merge

Rebasing your pull request is a clever bit of Git that lets you say “Hey, I know I started this feature branch last week, but other people made changes in the meantime. I don’t want to deal with their changes coming after mine and maybe conflicting, so can you pretend that I made it today?”

The trick here is each Git commit not only contains a set of changes to files, but also a link to the “parent” commit — the commit those changes should be applied to. Because each commit has a parent, Git can always follow the chain of history.

When you make a branch from master, the parent of your branch is the current commit on master. Then development continues on your branch and on master. When you merge your branch, the merge commit is a special commit that has two parents: The last commit from your feature branch and the newest commit on master, which “closes” the branch.

When you rebase your branch, what you’re doing is changing the parent commit your branch was based on to be the most recent commit on master. Then when you merge your feature branch, it sees that your commits all come after what’s on master, so it just adds them to the chain.

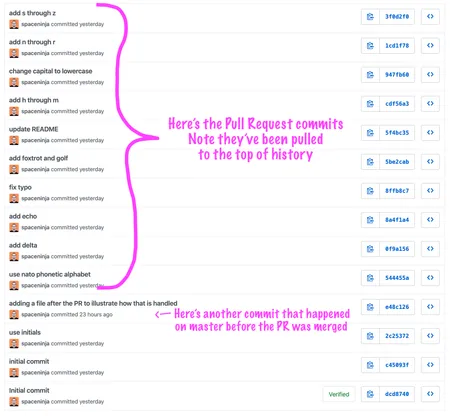

Screenshot of Git history showing a commit that happened on master before the pull request was merged, followed by a large group of pull request commits.

However, as with the merge commit option, all your messy incremental commits are retained. It’s just that instead of being scattered through history, they’ll all come in a batch at the end.

So for our purposes, both the rebase and merge commit options leave a messy Git history with no real benefit. Let’s look at our third option to see how it helps.

Squash and Merge

Squash is a Git option to collapse all the incremental commits in your pull request into a single commit.

If you use the GitHub interface, it will squash all your commits into one. Then it will give you the option to edit the commit message. It will even pre-populate your new message with all the messages of the commits being squashed. Then you can do something like adding a list of all the incremental changes if you want to preserve it.

If you use the command line, you have the option of only squashing some of the commits, or even changing the order they’re applied. It’s a nice option, but I’ll admit I rarely find myself needing to do anything more than simply combining all my commits into one.

For our purposes — a developer merging a short-lived feature branch that no one else is depending on — squashing all the commits like this is ideal.

Screenshot of Git history showing a commit that happened on master before the pull request was merged, followed by a single squashed commit for the entire pull request.

It gives us a nice clean commit history with a single commit representing all the work that happened on the feature branch. There are no annoying merge commits. There’s no pointless incremental lint fix commits. Just one commit with a useful commit message.

Conclusion

Squashing and merging isn’t the right answer for every situation. In particular, if you need a record of one branch being merged into another, or if you have long-lived feature branches that other people depend on, your team may prefer merge commits as a more accurate record of history.

However, for developers working alone on short-lived feature branches that will be deleted after merging, squashing is ideal. It results in a cleaner Git history that’s easier for the team to read.

The Git docs say:

One point of view on this is that your repository’s commit history is a record of what actually happened. It’s a historical document, valuable in its own right, and shouldn’t be tampered with. From this angle, changing the commit history is almost blasphemous; you’re lying about what actually transpired. So what if there was a messy series of merge commits? That’s how it happened, and the repository should preserve that for posterity.

The opposing point of view is that the commit history is the story of how your project was made. You wouldn’t publish the first draft of a book, and the manual for how to maintain your software deserves careful editing. This is the camp that uses tools like rebase and filter-branch to tell the story in the way that’s best for future readers.

In conclusion, as a rule of thumb, most pull requests should squash down to a single commit with a well-written message explaining why a change is happening.