How to use @font-face to avoid faux-italic and bold browser styles

TL;DR: Did you know that if you declare a custom font, the browser will try to fake the bold and italic styles if it can't find them?

Image credit: Fabien Barral

Did you know that if you declare a custom font using @font-face, the browser will try to fake the bold and italic styles if it can't find them? This is a clever little feature that avoids a scenario where a designer specifies a font and is then confused that bold and italics don't work, but it can be very confusing if you actually have a bold or italic version of the font. In this article, I'll walk you through how to properly load your font files to avoid the browser's faux-italic and faux-bold styles.

The Problem

First, to clarify: A font is a file containing a particular typeface, which is a particular weight or style of a type family. eg, garamond-bold.ttf is the font copy of Garamond Bold, a typeface from the Garamond family. In CSS terms, you load a font file using @font-face declarations, which append that font to a font-family.

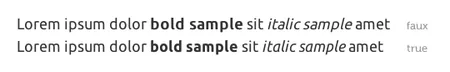

The problem, as you can see in this screenshot, is that if you only load one font into the family, then the browser doesn't know what to do when it's asked to render a bold or italic section using that font. It solves this by creating a faux-bold style by stretching the letters horizontally, and a faux-italic style by slanting the letters.

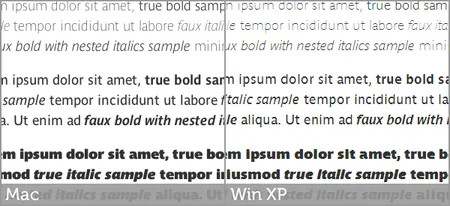

Figure A: Comparison of faux browser styles and true typefaces

The browser's brute-force approach to creating these faux styles leaves a lot to be desired. In particular, note the proper italic font includes a variant lowercase 'a' without the ascender, and bold characters have an even thickness to the stroke, rather than the wider vertical strokes on the faux-bold.

The Wrong Solution

The common technique shared by many font services like FontSquirrel or WebINK is to create additional @font-face declarations, creating a new font-family definition for each font weight and style. Then you apply the regular font to the target, and write rules to apply the bold or italic fonts on any nested elements, like so:

@font-face {

font-family: 'UbuntuRegular';

src: url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.svg#UbuntuRegular') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'UbuntuItalic';

src: url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.svg#UbuntuItalic') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'UbuntuBold';

src: url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.svg#UbuntuBold') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'UbuntuBoldItalic';

src: url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.svg#UbuntuBoldItalic') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}

.test {

font-family: UbuntuRegular, arial, sans-serif;

}

.test em {

font-family: UbuntuItalic, arial, sans-serif;

}

.test strong {

font-family: UbuntuBold, arial, sans-serif;

}

.test strong em {

font-family: UbuntuBoldItalic, arial, sans-serif;

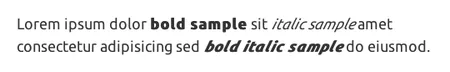

}However, doing that actually results in what you see here, where the browser still applies its own faux bold and italic styles on top of the hard-coded bold and italic fonts you defined.

Figure B: Faux browser styles applied on top of proper italic and bold fonts

To solve that problem, you reset font-weight and font-style on the nested styles to disable the faux browser styles.

.test {

font-family: UbuntuRegular, arial, sans-serif;

}

.test em {

font-family: UbuntuItalic, arial, sans-serif;

font-style: normal;

}

.test strong {

font-family: UbuntuBold, arial, sans-serif;

font-weight: normal;

}

.test strong em {

font-family: UbuntuBoldItalic, arial, sans-serif;

font-style: normal;

font-weight: normal;

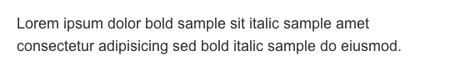

}And it seems to work perfectly! Your custom bold and italic fonts are loaded properly, and the faux styles are nowhere to be seen! The problem is that if your custom font doesn't load for some reason, the browser is no longer applying bold or italic styles to the fallback font.

Figure C: No bold or italic styles if custom font fails to load

So I think we can agree that this solution doesn't work. It requires a lot of CSS to override built-in browser styles, and it breaks completely when the custom font doesn't load. Luckily, there's a better solution:

The Right Solution

Instead of defining separate font-family values for each font, You can use same font-family name for each font, and define the matching styles, like so:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Ubuntu'; /* regular */

src: url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-R-webfont.svg#UbuntuRegular') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'Ubuntu'; /* italic */

src: url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-RI-webfont.svg#UbuntuItalic') format('svg');

font-weight: normal;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'Ubuntu'; /* bold */

src: url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-B-webfont.svg#UbuntuBold') format('svg');

font-weight: bold;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: 'Ubuntu'; /* bold italic */

src: url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.eot');

src: url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.woff') format('woff'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'),

url('Ubuntu-BI-webfont.svg#UbuntuBoldItalic') format('svg');

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

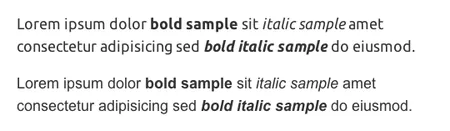

}Then all you need to do is apply that single font-family to your target, and any nested bold or italic styles will automatically use the correct font, and still apply bold and italic styles if your custom font fails to load.

Figure D: Properly defined italic and bold fonts with fallback styles

You can see a live example of these problems and the final solution on the demo page.

Seriously, Microsoft?

Figure E: Comparison of @font-face on Macintosh and Windows XP

Also, I know it's old news that type rendering on Macintosh is better than Windows, but seriously, when I see results like this (look at the lowercase 'd' - it's a travesty!), I consider telling my clients it's not worth it, because their beautiful custom fonts are going to look awful to over half the visitors to their website. I've heard Windows 7 has better rendering, but I don't have a copy to test. All I can do at this point is trust that things will continue to improve, and enjoy how pretty things look on my Mac.