What IS Flexbox?

TL;DR: An elegant layout method for a more civilized age.

Flexbox is a new layout mode in CSS3. The previous version of CSS defined four layout modes:

- block layout for laying out documents

- inline layout for laying out text

- table layout for laying 2D tabular data

- positioned layout for explicit positioning

Now, you might be thinking “What about floats? They’re used for layout all the time!” Good point, but floats were never intended for layout. They were a CSS recreation of the old align attribute in HTML. Clever web developers found ways to abuse them to create complex layouts, but they’re limited and buggy — as anyone who’s wrestled with a clearfix can attest.

CSS3 introduced two new layout methods as an alternative to abusing floats and tables:

-

Grid layout divides space into columns & rows. Like table layouts, but better! The Grid layout spec is still being developed, and isn’t ready for use yet.

-

Flexbox layout distributes space along a single column or row. Like float layouts, but better! The Flexbox spec is finished and enjoys excellent browser support today.

A Very Brief History of Flexbox

As I was writing this, I realized I didn’t actually know what motivated the creation of these new layout methods. I wrote to Tab Atkins Jr., the primary author of the Flexbox and Grid specifications, and he told me this:

In the late aughts, Mozilla tried to formalize its XUL layout model as Flexbox. The earliest draft I know of is from 2009, but I think it started back in 2007. Nothing much came of this; WebKit partially implemented some of it, and even Firefox didn’t match its own spec, because things were woefully underspecified.

Then in 2010 or so I joined the WG, and one of the first things I did was dust off Flexbox and fix everything. (Read: rewrite the entire goddam thing.) A year or two after that, Microsoft submitted its first draft of the Grid Layout spec, and I muscled my way in and took that over too (rewriting that whole thing as well).

My goal in doing Flexbox and later Grid was to replace all the crazy float/table/inline-block/etc hacks that I’d had to master as a webdev. All that crap was (a) stupid, (b) hard to remember, and (c) limited in a million annoying ways, so I wanted to make a few well-done layout modules that solved the same problems in simple, easy-to-use, and complete ways.

In a nutshell: Flexbox and Grid were created explicitly to replace float and table layout hacks.

There are (not) 3 Flexbox Specs

You may have heard there are three Flexbox specifications. (Which makes me think of this scene from Star Trek:)

Don’t let that scare you away. Yes, there are three versions of the spec, but only one of them really matters:

-

The old 2009 spec —

display: box— is no longer relevant. -

The 2011 "tweener" spec —

display: flexbox— was a draft spec, only implemented in IE10. You should avoid it if possible. -

The final 2012 spec —

display: flex— is the new hotness, with excellent browser support (see below).

Note: Each spec used a different keyword for the display property, which means if you’re reading an article about Flexbox, it’s easy to figure out which version of the spec they’re discussing. If you see anything other than display:flex, it’s an older article and can be ignored.

Flexbox Layouts Go in One Direction

Sorry, dumb joke. I mentioned that Flexbox lays items out in a single row or column. Let’s talk about what that means:

Image credit: Flexbox Cheatsheet

A Flexbox layout consists of a flex container that holds flex items. The flex container can be laid out horizontally or vertically. This is referred to as the main axis.

Image credit: Flexbox Cheatsheet

The direct children of a flex container are laid out along the main axis. These children can “flex” their sizes, growing to fill unused space in the container, or shrinking to avoid overflowing.

By nesting multiple flex containers with different orientations, you can achieve complex layouts.

Flexbox Properties

There are too many properties to get into here, so I will refer you to the excellent CSS Tricks Flexbox Guide, which does a great job of introducing all the properties.

Don’t be overwhelmed. There are a lot of options, but Flexbox includes a set of intelligent defaults so you can create a powerful layout with very little code. Here’s an example:

.flex-container {

display: flex;

}That one line of code does all the following:

- Treats

.flex-containeras a flex container. - Treats all direct children of

.flex-containeras flex items. - Flex items will be laid out in a horizontal line.

- Flex items will be laid out in source order.

- Flex items will be laid out starting from the left side of the flex container.

- Flex items will be sized based on their regular

widthproperties. - If there’s not enough space for all the flex items, they will be allowed to shrink horizontally until they all fit.

- If they need to shrink, each item will shrink equally.

- Flex items will all stretch vertically to match the height of the tallest flex item.

That’s quite a bit of logic for a single line of CSS! You can change any of those, but I wanted to give you a taste of how powerful Flexbox can be with no extra work.

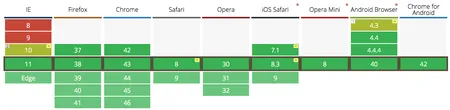

Browser Support

As of August 2015, browser support is excellent! The current Flexbox spec is fully supported in all modern browsers, including mobile, IE11 and Edge.

IE10 also supports Flexbox, but uses the tweener spec (display:flexbox).

What About Older IE Versions?

I have some ideas

Best-case scenario? If you don’t mind the non-Flexbox browsers getting a different layout, then you don’t need to do anything. This is called graceful degradation and is certainly the easiest approach.

When browsers see a rule they don’t understand — like display:flex — they ignore it entirely. This is great for us, because it means all Flexbox properties will be ignored. A flex container and items will fall back to their default behavior, likely display:block.

As a result, non-Flexbox browsers will get a vertically-stacked mobile-style layout. All the content will still be accessible and functional, it just won’t be laid out the same as modern browsers.

Graceful Degradation with Modernizr

If that won’t work, you can provide a fallback float-based layout using Modernizr. Modernizr is a JavaScript library that evaluates the browser’s capabilities and adds a set of classes to the body element, which allows you to scope CSS based on feature support.

If a browser doesn’t support Flexbox, then a no-flexbox class will be added. Here’s a simple example of what your CSS would look like:

.parent {

display: flex;

}

.child {

flex: 1;

}

.no-flexbox {

.child {

float: left;

width: 50%;

}

.parent::after {

@include clearfix();

}

}The advantage to this approach is your fallback code is scoped to the no-flexbox class. As a result, when the day comes that you can drop support for non-Flexbox browsers, you can easily delete all the no-flexbox code and your site just keeps working the same way. No messy refactoring needed.

A note about IE10: The flexbox test in Modernizr 2.8.3 returns true in IE10, which means that it wouldn’t see your fallback styles. You can fix this a number of ways: IE10-specific code in a conditional comment, using a tool like Autoprefixer, or by simply using Modernizr 3, which has an improved flexbox test that properly excludes IE10. Learn more.

Conclusion:

Flexbox is a layout mode added in CSS3 to replace hacky float and table layouts. It comes with a clever set of defaults that make it easy to create complex layouts with relatively little code. It’s stable, easy-to-use, and well-supported.